Visit Aztlan Reads and stay up-to-date on all things Xicana/o literature..

Flight to Freedom: A Story of Resistance

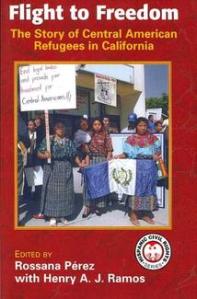

Rossana Pérez in Flight to Freedom: The Story of Central American Refugees in California documents the stories of eight key Salvadorans who were integral to the formation of a political resistance movement in the United States whose primary purpose was to bring an end to the civil war raging in El Salvador. As a result of American policy designed to neutralize Communist influence in the Western hemisphere, a conservative estimate of over 80,000 Salvadorans were killed and 9,000 were “disappeared” as the United States engaged El Salvador in a low-intensity war of hegemony.

Thousands of Salvadorans were forced to flee their native country in a “Flight to Freedom” evoking memories of the Underground Railroad. Due to the unique political circumstances that befell Salvadoran refugees, they immediately began organizing sanctuary and solidarity movements to defend themselves in the United States as well as to nurture a powerful voice to the deafening silence that was occurring in El Salvador. It is in this context, then, that Pérez situates the Salvadoran experience.

The eight testimonios serve to inform a unique historical experience in oppositional resistance movements in the United States that previously had been undocumented. This new political struggle was aimed at not only improving the socio-political conditions refugee Salvadorans faced in the United States, but of transforming their country of origin. It seemingly appeared to be a break from the Chicano Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, which focused its struggle on conditions within the United Sates. More importantly, this new Salvadoran movement was a multi-ethnic effort that saw many EuroAmericans contribute to the international struggle to alter American policy vis-à-vis Central America.

The interviewees were deeply insightful about their experiences and provided a unique contribution to the overall understanding of social movements in the United States. It was interesting to note that despite the language barriers and political uncertainties the Salvadoran refugees faced in the United States upon their initial arrival, they were able to situate themselves within the U.S. political landscape since many of the leaders came from middle-class backgrounds, which facilitated their determination for social justice.

Their middle-class background helped to inform their natural inclination to fight for their dignity and rights in a foreign country. That many of the initial leaders of the sanctuary and solidarity movements came from middle-class backgrounds in El Salvador, but were only able to affect a social justice collective behavior after being forced to flee, was reminiscent of the revolutionary activities of Ricardo Flores Magón and the Partido Liberal Mexicano prior to the start of the Mexican Revolution of 1910.

In the overall narrative, Flight to Freedom is a significant account to better understand the history and experiences of Salvadorans in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. As noted in the testimonios, the trials and tribulations faced by the Salvadoran community was substantially informed by American foreign policy. It is obvious that a further study is needed to address the issues that the sanctuary and solidarity movements faced as they challenged both American and Salvadoran policy. For the most part, the narratives chronicled the positive outcomes of their political work without referencing any of the challenges they faced under the political environment of the Reagan administration. However, the contribution by Pérez lays the foundation for further inquiry into this matter.

While probably not the scope of the interview process, it would have been instrumental to have focused attention on the impact American society has had on the children of Salvadoran refugees. Alicia Mendoza was the only one to substantially address the unhealthy influences American society had on the children, whom many have been tragically immersed into the U.S. gang culture (142). The fact that Salvadoran refugees struggled for equal access, dignity, and human rights both here in the United States and in El Salvador, one must ask the question about what role U.S. institutions and domestic policy played in the development of the destructive forces of gang-culture within the children of the Salvadoran refugees?

Rossana Pérez and Henry A.J. Ramos hoped to make this reading accessible to younger readers to inspire them to follow an activist path in law, education, or community organizing. This is one of the greatest contributions of this seminal undertaking for it situates the larger scope of the Central American Studies Program at California State University, Northridge. This is a history that is long overdue. It also a history of the role women played as equal partners in the struggle for human rights.

This narrative should serve to inform Chicana/o Studies as to the type of scholarly-activism it should be undertaking. As Pérez states about the general history of massacres and political crimes committed against Indigenous peoples, Americans can no longer “live much longer in denial of this history” (Preface xv). Flight to Freedom is merely one template to remediate the legacy of American historical amnesia.

About the Author: David is a third generation Chicano currently completing his Master’s degree in Chicana/o Studies at California State University, Los Angeles. Main areas of study: Chicana/o Movement, Chicana Feminist Thought, Chicana/o Studies History, Social Movement Theory, Chicana/o Oral History, Chicana/o History, and Chicana/o Intellectual History.

Filed under Central American Studies

Rethinking La Familia in Richard T. Rodríguez’s Next of Kin

The 38th Annual of the National Association for Chicana & Chicano Studies (NACCS) was held on March 30-April 2, 2011 in Pasadena, CA. This year’s theme: Sites of Education for Social Justice focused on the issues that impact Chicana/o education by examining the various methods through which educators, academic and activists, engage in educative acts that promote social justice. The four-day event included exhibitor showcases, plenary discussions, the premiere of Chicana/o films, a political tardeada to save ethnic studies, and a book award.

In particular, the NACCS Book Award for 2011 honored Richard T. Rodríguez for Next of Kin: The Family in Chicano/a Cultural Politics (2009). Next of Kin explores the concept of La Familia within the political and cultural discourse of the Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Drawing upon both a traditional Chicana Feminist and an emerging Chicana/o Cultural Studies critique, Rodríguez argues that notions of kinship and family within a Chicana/o cultural narrative is fundamentally heteropatriarchal as expressed through the aesthetics of Chicana/o literature, film, music, and art.

In perhaps the first systematic review of la familia within the framework of the archived documents that emerged during the Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, Rodríguez critically scrutinizes the symbolic cultural production of la familia de la raza. In particular, a closer inspection of the guiding political manifesto of the Chicano Movement, El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán, within the context of a Chicana Feminist and Queer Theory reveals Chicano Nationalism as “institutionalized heterosexism” (Rodríguez, 8).

In early 1969, at the National Chicano Youth Conference, sponsored by the Crusade for Justice, several Chicanas attempted to articulate a gendered position of empowerment by focusing on the question of the “traditional role of the Chicana in the Movement and how it limited her capabilities and her development” (Sonia A. López, 1977). By voicing this important and neglected issue, Chicanas recognized the impending ideological dichotomies embedded in the Chicano Movement. At the conclusion of the conference, however, the Chicana representative reporting to the conference group declared the following statement: “it was the consensus of the group that the Chicana woman does not want to be liberated” (Rodríguez, 25).

Such referendums of gender exclusion created perceptions of a Chicano kinship and family network that needed to be wrestled away from the ideals of Western academic studies (Rodríguez, 24). In other words, Chicanos were intent on reformulating the family on one based on the concept of resistance that would in time create the catalyst for social and cultural change. The romanticized view of the Chicano family, nonetheless, was essentially seen through a masculine lens of at the expense of the nuances of the larger portrait of what really constituted la familia. A closer look at the principles of kinship and family as articulated by Chicano Movement rhetoric and symbolism exposed the limitations of “political familism” (Rodríguez, 24).

While much is articulated about the concept of Aztlán within studies of the Chicano Movement, la familia was previously observed as an idealized representation of Chicana/o cultural survival. By critically assessing the portrait of the Chicana/o family within the landscape of literary, artistic, and social mediums, Rodríguez extends the narrative of cultural critique and by extension the narrative of cultural inclusion of the “Other” within the framework of Chicana/o Studies vis-à-vis the Chicano Movement. The portrait of the Chicano family has been primarily defined within the ethos of Chicana/o Nationalism as referenced through the work principally of Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales of the Crusade for Justice.

In the chapter, The Verse of the Godfather, Rodríguez addresses the “politics of masculinity” within a contemporary popular cultural motif (Rodríguez, 96). In exploring the so-called “mainstream” Chicano hip-hop, Rodríguez contends that the music internalizes negative notions of masculinity and family. Rodríguez, furthermore, elucidates the “gendered factionalism” that hip-hop is implicitly supporting especially in the music of Kid Frost, among others (Rodríguez, 122). Thus, the Chicana/o voice and image presently seen and heard in mainstream media is antithetical to the framework of the Chicano Movement. As such, negative masculine representations continue to exclude and silence concepts of gender and sexuality.

In The Last Generation: Prose and Poetry, Cherríe Moraga links the nationalism of the Chicano Movement with her conceptual framework of a Queer Aztlán. As an extension of Chicana/o Nationalism’s social thought process, Moraga acknowledges that a divided house will not stand. As such, Moraga reminds us that the freedom of men, be they gay or straight, is intricately connected to the freedom of women. Chicano Nationalism is the principle tool that binds us a together as a people, as a family. Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales and Cherríe Moraga are central to understanding that as nationalism evolves so does family. However, the lens of the Chicana/o family must be situated within the Chicana/o framework of resistance; for people will never be free if any of its members remain in submission. It is in this context, then, that Rodríguez exposes the limitations of the symbolism and language attached to the Chicano Movement.

While most Chicana/o Studies scholars would argue that in the larger context the Chicano Movement reflected an anti-hegemonic attempt to dismantle institutionalized racist structures in U.S. society, Rodríguez would argue that it did so within the ethos of a masculine dimension. Thus, while there was an urgent and necessary call to “arms” among Chicanos to change existing structural dynamics, the Chicano struggle of the 1960s and 1970s excluded from its political narrative the question of gender and sexuality from its strategies of self-determination.

As the recipient of the 2011 NACCS Book Award, Next of Kin deservingly stands out as one of the best recent contributions to the field of Chicana/o Studies. Next of Kin is an excellent addition to any Chicana/o Studies book collection.

About the Author: David is a third generation Chicano currently completing his Master’s degree in Chicana/o Studies at California State University, Los Angeles. Main areas of study: Chicana/o Movement, Chicana Feminist Thought, Chicana/o Studies History, Social Movement Theory, Chicana/o Oral History, Chicana/o History, and Chicana/o Intellectual History.

Filed under Chicano, Cutural Studies, Gender Studies, Queer Studies

Saludos Aztlán

Saludos Aztlan!

Welcome to Aztlan Reads. We came into existence in a relatively quick and surprisingly amazing way. A conversation on twitter.com between @anneperez and @xicano007 about Xicana/o books prompted the searchable hashtag: #aztlanreads. Within hours of creating the #aztlanreads hashtag, many friends/allies on twitter.com with an interest in Xicana/o Studies began to contribute their personal favorites. It was beautiful to see so many Xicana/o titles and the meaning that they held for some contributors who shared that information as well.

The initial idea behind an #aztlanreads hashtag was to facilitate easy access to an expansive list of Xicana/o fiction and non-fiction literary work that could be used for our personal reading enjoyment or for academic research purposes. The books could be on any topic be it history, women’s studies, cultural studies, literature, etc. The next step, of course, was to create a separate and more accesible twitter feed to continue our endeavor. So @aztlanreads was created. One goal for this project is to promote literacy within the Twitter community and beyond. Another goal is to let the world know that Xicanas and Xicanos are reading and thereby asserting that we are not an uneducated group of people. A third goal is to debunk the myth that there is small body of work by and for Xicana/os and to debunk the myth that these works are inaccessible.

We are a also a hard working and intelligent community. From hashtag to twitter feed to website! Thanks to the dedicated work of @ginaruiz, @Chicano_Soul and @mexicanwoman, a simple conversation about a common interest in Chicana/o Studies reading has metamorphosed into a budding website.

Those of us supporting Aztlan Reads hope that our endeavor becomes one of the largest databases of Xicana/o Studies fiction & non-fiction work. It is made available by a community of readers and therefore sacred. We invite you to join us by contributing your recommendations and reviews. This website will eventually be a site for community book readings and discussions, as well as a forum for Xicana/o authors to discuss their own personal work.

We hope that you’ll visit often.

Filed under Chicano